By Chris Lang. Presentation at a conference in Berlin: “Sustainability certificates for agroenergy: Guardrail or lubricant for trade with regrowing energy resources?” organised by Brot für die Welt and FDCL, 4 October 2008.

The presentation is available here as a pdf file (3.5 MB).

I’ve been asked to look at the question “Did the FSC pass the practical test or is it on the wrong track?” I was thinking about this coming here this morning on the train from Frankfurt and I may have got a little carried away with the train metaphors. The background to this slide is what an FSC certified eucalyptus plantation might look like from a moving train.

Howard Zinn has a good line about trains: “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.” When we’re thinking about FSC and certification I think important questions to keep in mind are: Who are we working with? and Who are we supporting? Are we supporting the pulp and paper industry which is looking for a green seal to justify and expand its destructive operations, or are we supporting the struggles of local communities who are losing their land and livelihoods to the expansion of monoculture tree plantations?

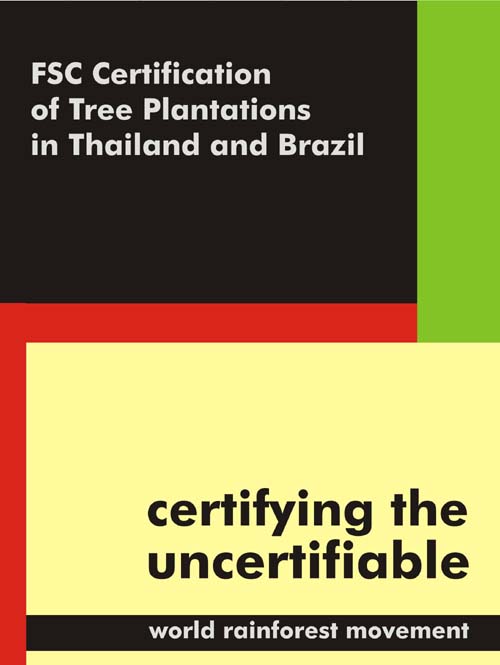

I’m going to look at three problems with FSC. In fact they all apply to any voluntary certification system, not just to FSC. Before going any further, I should point out that FSC is the best timber certification system out there. This doesn’t mean that FSC is any good, it just means that the others are even worse.

First, the certification system has to be credible. It has to have a clear set of standards that can be consistently interpreted. This is not the case with FSC. The company carrying out the certification assessment must be clearly separated from the company it is assessing. In the case of FSC, the certifying bodies are paid directly by the company wanting to get certified. There is a clear conflict of interest at the heart of the FSC system. The system must have clear labels, so that the consumer knows what it is that he or she is buying.

Second, the proliferation of certification systems confuses customers. It is almost impossible to keep track of which labels are meaningful and which are greenwash.

Third, voluntary certification is powerless to prevent a company that has no interest in “improving” from carrying on business as usual.

Looking at the first problem, credibility, I’m just going to take the example of criterion 6.3. In order to qualify for certification, a forestry or plantation operation has to comply with all of FSC’s Principles and Criteria. Criterion 6.3 should exclude the certification of industrial tree plantations.

Criterion 6.3 talks about regeneration, diversity, natural cycles and forest ecosystems. So how can FSC certify this? There is no diversity. There is no natural cycle. The plantation has been clearcut and will only continue to exist as a plantation if new seedlings are planted. There is no forest regeneration and succession.

This is Veracel in Brazil, which was certified in March 2008. At its 2002 General Assembly, FSC passed a motion which stated that a Plantations Review was needed. Six years later, nothing has changed.[1]

Surely, you might be thinking, FSC’s labelling system is clear, isn’t it? If a product comes from a certified operation, it can carry the FSC logo.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. There are seven different FSC labels. The one at the top left is straightforward. It means that the product consists of 100% FSC-certified wood. The label at the top right indicates that the product consists of 100% recycled material, which has the unfortunate side-effect of meaning that none of the wood in the product came from an FSC-certified operation.

But with the “mixed sources” label, things get really problematic. I’m not going to go into detail about what each of these labels means. The point is that a consumer buying paper with one of these labels is not going to know what it means. The reality is that a product carrying one of these labels might contain as little as 10% FSC-certified material. The rest comes from recycled material and/or something called “controlled sources”, which basically relies on companies telling us that their operations are not controversial. FSC’s third party certification system starts to look a lot more like self-certification.

FSC’s confusing labels are only the beginning if you’re a conscientious consumer. You might be faced with lots of other labels. (Some of these might be perfectly good certification systems – others are not. As a consumer, you just don’t know.)

Perhaps the worst problem with voluntary certification is that it is powerless in the face of companies that are simply not interested in certification. This, for example, is in southern Laos, where a series of Vietnamese companies are clearing villagers’ forests and common lands to make way for rubber plantations. Certification can do nothing to stop this.

Neither can FSC do anything about this – a company in Thailand called Advance Agro. You can search on FSC’s website for this company, but you will find no mention of Advance Agro or the problems that the company has caused for local communities. The company is not certified and (as far as I know) has no interest in getting certified.

Here, my argument changes slightly, because this monoculture is FSC certified. In fact, the company that planted this monoculture (and hundreds of thousands of hectares of almost identical plantations in South Africa) is Mondi, the “Gold Sponsor” of FSC’s General Assembly, which is currently taking place in South Africa.

Another FSC certified monoculture – this one belonging to Veracel in Brazil.

FSC can do nothing to prevent this. This is how Veracel bulldozed forests to make way for its plantations. It did so in 1993, which is fine, according to FSC – even though it was illegal under Brazilian law.

FSC has a 1994 cutoff date for clearing forest. Had Veracel cleared this area of forest in January 1994, it could not (at least in theory) be certified. The reality is that Veracel has continued to clear areas of forest for its plantations since 1994, but the certifying body, SGS, did not seem interested in looking into this sort of detail.

Another FSC certified monoculture tree plantation, this time the company responsible is SAPPI and the plantations are in Swaziland.

I think what is worse than all of this, is that FSC can do nothing to support local struggles against industrial tree plantations. This is a protest in Espirito Santo province in Brazil by people affected by monocultures planted by Aracruz, a Brazilian-Norwegian pulp company. Aracruz’s monoculture eucalyptus plantations have taken people’s land, dried out water courses and destroyed local livelihoods over an area covering hundreds of thousands of hectares.

In fact, FSC undermines this sort of struggle by certifying the very plantations that local people are protesting about. Aracruz is currently trying to get FSC certification. It has hired the consulting firm ProForest to prepare for certification and is planning to carry out pre-assessments later this year or early next year.[2]

To return to the question I was asked to look at: “Did FSC pass the practical test or is it on the wrong track?”

The answer is simple:

FSC is the wrong train, it’s on the wrong track, it’s going backwards and it’s been hijacked.

Footnotes:

[1] Things may be about to change – for the worse. In April 2008, FSC’s Board produced a draft version of a series of amendments to the Principles and Criteria. They proposed deleting Criterion 6.3, which would make the certification of industrial tree plantations even easier under the FSC system.

[2] Aracruz plans to hire SmartWood/Imaflora to carry out the certification, but no contract has been signed to date.

It might be prudent to do deeper research on some of the examples stated in your article. The Advanced Agro case mentioned states that they are not listed on the FSC site. That is true. What is not true is that they are not interested in obtaining FSC certification.

AA have been trying in vain to obtain FSC certification – the very example that you have shown on your website is the reason why they have not been able to obtain FSC approval. This is proving to be a very big headache for them. My understanding is that current FSC – FM rules involve an analysis of the surrounding environment and persons potentially affected.

I am not an expert on FSC, nor do I claim to be one – but it is clear that the principles are clear. Cultivate forests for general utilization for mankind, and leave the rain forests alone.

Your thoughts?

@Suresh Subramaniam – Thanks very much for this comment. As I pointed out in the presentation, I didn’t know that AA had been trying to get FSC certification. Thanks for the information! But this only reinforces my point. FSC and its certifying bodies have made no public statement about the failure of AA to get FSC certification. All that FSC can do is decline to issue an FSC certificate. FSC can do nothing to address the social and environmental impacts of AA’s plantations and pulp mill operations and has not even attempted to alert anyone outside a very small number of “stakeholders” to these problems.